Imagine now that you are visiting a faraway desert and encounter a giant green heap of leaves on the ground, perhaps approaching your own stature. Clearly it is a plant, but what is it, how does it come to appear this way and how is it possibly well-adapted? These may be some of the questions that outside explorers first asked when encountering an unconventional plant in the coastal Namib Desert of southwest Africa. Though it already carried names in the indigenous Nama, Damara and Herero languages, it would be given the name of Welwitschia mirabilis in honour of the Austrian botanist Friedrich Welwitsch who made it known to the outside world. And indeed the plant is as wonderful as the scientific species name of “mirabilis” means to tell us, but we need to look at the different life stages of the Welwitschia (pronounced “Vel-vi-chee-a”) to understand.

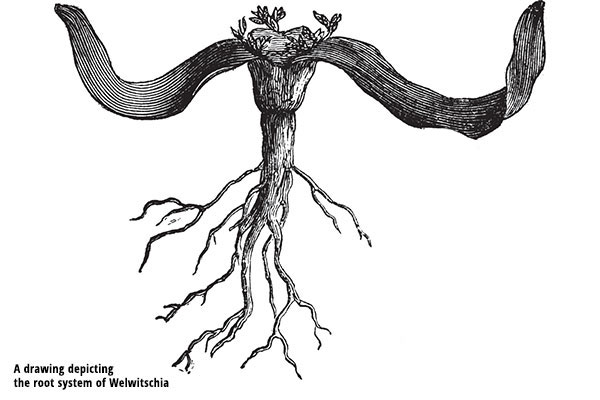

After germination and initial establishment, a Welwitschia looks like this, with two tough, strap-like leaves opposite each other and growing out of what appears to be a narrow wooden stump. The stump is in fact the original stem of the plant, the top tissue of which simply stops growing and dies. The leaves continue growing out of the fringes of the stem, in fact continuously over the life of the plant.

Theoretically the leaves could become many metres in length but the wind tosses them about as they grow and causes the tips to fray and wear. The fraying also splits the leaves from the tips down towards the base, giving the impression that the plant has multiple leaves when in fact it still has but two.

Meanwhile, the base out of which the leaves grow continues to grow in size. Presumably due to idiosyncrasies of local conditions and circumstances, the base can become quite distorted over time, causing the leaves to also grow in a distorted fashion, contributing further to their splitting and making them appear to grow out of multiple points of origin. Over time, Welwitschia can become quite a morass described by some as a ‘desert octopus’!

This explains the appearance but how is this plant well-adapted to the harsh and arid environment where rain seldom falls? There are two things that aren’t quite evident to us at first glance. The first is that the plant has a taproot that extends some distance below the soil surface, allowing it access to underground water supplies.

The other is in the leaves themselves. Welwitschia’s sometimes huge leafy surface area can capture moisture from coastal fog, conducting the dew down to the rootstock. In this way it can apparently absorb the equivalent of 50 mm of rainwater through dew alone. It can also absorb water directly through the leaf surfaces! These adaptations would presumably serve the Welwitschia well as it is said by some to be able to attain an age of 1,500 years or more! As such, it lives up to its Afrikaans name of tweeblaarkanniedood, which translates fittingly into “two-leaved die-hard”! Welwitschia’s tenacity and peculiarity to this region have even earned it a place on Namibia’s coat-of-arms.

There is much else to appreciate about the Welwitschia. I was keen to see it during a visit of the Twyfelfontein region of Namibia in 2013 and I think you’d enjoy seeing this bizarre plant too!

We look forward to seeing various specimens of Welwitschia both young and advanced in age along with many other interesting sights when we visit Namibia on our next tour! Click here for more information.