It has long been recognized that Polar Bears will opportunistically exploit various land food sources during the ice-free season. We had a chance to witness a Polar Bear demonstrating its opportunistic (and impressive) foraging abilities ourselves last summer during Worldwide Quest’s Canada’s Northwest Passage expedition cruise. We were visiting the internationally significant migratory bird sanctuary of Prince Leopold Island, which is situated in Lancaster Sound at the junction of Prince Regent Inlet and Barrow Strait.

Route of Quest’s Northwest Passage cruise August 2017,

showing location of Prince Leopold Island

showing location of Prince Leopold Island

The island is flat-topped with fantastic sheer limestone and sandstone cliffs rising almost 300 metres from the sea. The cliffs provide an abundance of ledges and crevices for four nesting seabird species. About 100, 000 pairs of Thick-billed Murres, 22,000 pairs of Northern Fulmars, 29,000 pairs of Black-legged Kittiwakes, and 4,000 pairs of Black Guillemots nest on the cliffs. The island’s location is particularly attractive as sea ice breaks up early in spring in the adjacent waters, resulting in plankton blooms occurring here much earlier than in other regions of the high Arctic. The plankton blooms provide plentiful food for fish and crustaceans, which in turn are eaten by seabirds. The nutrient-rich waters also attract marine mammals including Beluga, Bowhead Whale, Narwhal, Walrus, Ringed Seal, Bearded Seal and Polar Bear.

View of the sheer cliffs of Prince Leopold Island

Photo: Martyn Obbard

Photo: Martyn Obbard

Some of the 100,000 pairs of Thick-billed Murres on their nesting ledges

Photo: Martyn Obbard

Photo: Martyn Obbard

Thick-billed Murres play an important part of this story. When young Thick-billed Murres are ready to leave the nest, the father calls to them from the water at the base of the cliff. Young and adults have learned to recognize each other’s voice from the time the young hatched. The yet-flightless young respond by launching themselves from the nest ledge. The fortunate ones land safely on the water and soon re-unite with their fathers. The sound of young and adults whistling/calling to each other can be deafening! A few unfortunate young birds hit the shingle beach below the cliffs where, injured or dead, they fall prey to Glaucous Gulls or even Polar Bears. When our cruise visited Prince Leopold Island on 16 August 2017, there were many newly fledged young and father pairs on the water.

Thick-billed Murre fathers and fledged young in the water close to Prince Leopold island.

Photo: Martyn Obbard

Photo: Martyn Obbard

As we approached the island in Zodiacs, we saw a young bear lying on the beach. The bear soon got up, slowly walked towards the water, and swam along the base of the cliff. The bear continued to swim slowly along at the base of the cliff and drew close to some parent-young pairs.

Young male polar bear swimming at base of cliffs of Prince Leopold Island, approaching Thick-billed Murres

Photo: Boris Wise

The adult, then fledgling, of one pair dove and shortly the fledgling surfaced very close to the bear. The fledgling quickly dove again and the bear followed 2 seconds later. After a further 5 seconds the bear surfaced with the murre in its mouth!

Young male Polar Bear with captured Thick-billed Murre.

Photo: Boris Wise

The importance of foods obtained by bears during the ice-free season to a bear’s annual energy budget is somewhat controversial. Some feel that such foods will become even more important in the future in areas where the ice melts every year and the bears are forced ashore. However, others feel that bears cannot replace seals in their diet in any substantial way. Whichever way this plays out for Polar Bears in the future, we had an exciting demonstration of how opportunistic bears can be. A fledgling Thick-billed Murre wouldn’t contribute much to a polar bear’s diet, but the bear expended little energy in catching the murre so likely had a reward, even if a small one.

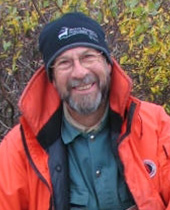

Martyn (Marty) Obbard is one of our team of onboard naturalists. Marty is an emeritus research scientist and the former resident bear biologist with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, and adjunct professor at Trent University (Peterborough, Ontario). He is a member of the IUCN-Species Survival Committee’s Polar Bear Specialist Group and is a former Chair of the Canadian Federal/Provincial/ Territorial Polar Bear Technical Committee. His field work focuses on Polar Bears and Black Bears, and he has published many papers detailing the demographics, genetics, and movements of these species.